Whatever comes to mind when you think of Cambodia, be it some vague connection the country had to the Vietnam war, the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge, ancient temple ruins in the jungle, or even orphans and Angelina Jolie, you’re probably selling it short. As often happens in travel, but particularly in Cambodia, our experiences challenged any box that we may have wanted to put this country into. We came expecting our visit to be a simple stopover to see an ancient world heritage site and we left feeling deeply moved and forever impacted by the country’s genuine, compassionate, and friendly spirit.

You can’t escape history in Cambodia. It confronts you through the broken down ancient temple ruins, bomb craters that have since become lakes that dot the country side, and even the camouflage jackets and pants that many people still wear.

The history of Cambodia encompasses majestic kingdoms that stretch back to the 6th century BC but today we are likely most familiar with the impact of the war, destructive dictatorial regimes, and rebel fighting that consumed so much of the last 50 years. The books, First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung (also now an excellent movie), and In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner are must-read first hand accounts of Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge.

The War Museum

On the outskirts of Siem Reap sits a tiny and unassuming war museum dedicated to preserving history and educating visitors on the damage and lasting effects the civil war had on the Cambodian people.

The museum has collected a number of military artifacts that are on display along side simple museum exhibits that tell tell an important human story. Unexploded ordnances still litter the countryside. Maps display their location and most that remain today are in the jungle where the hidden guerrilla forces fought off their captors for 20 years. We were told by our volunteer guide that last year was the first year that less than 100 people were casualties of these still hidden landmines. Put another way, nearly 100 people a year are killed or maimed by landmines in Cambodia some 40 years after the end of their civil war.

The museum was educational, eye-opening, and surprisingly not political. The volunteers and the exhibits themselves focus simply on showing and retelling the past. It was a profound and moving exhibit.

The Village on Stilts

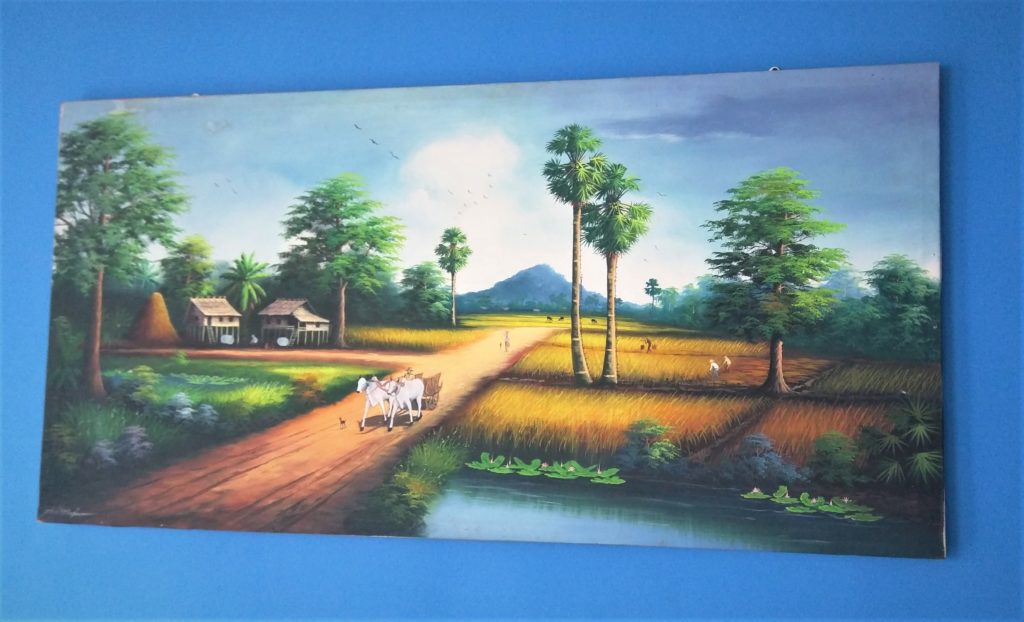

Cambodia sits between Thailand and Vietnam. In the middle of these two, perhaps more familiar countries, Cambodia shares some of the terrain of both – the tropical climate and jungle of Thailand and the farmlands and fields of Vietnam.

We visited Kompung Phluk, a village on the shores of Tonle Sap (a massive lake in Cambodia’s interior) that connects to the Mekong River. This region is seasonally flooded half the year and residents live (depending on when you visit) in floating or stilt homes. In the wet season, families live in the water, floating from home to home or to the forests to collect their crops. In the dry season (when we visited) the village is stacked upon high stilts and the children play in the dirt and the sand.

As we walked through the village, children were everywhere, playing and working, and often stopping to smile and say “hello” as you passed by.

The village has been continually inhabited for several hundred years and the residents are peasants tied deeply to the land and its cycle of water and drought.

Further downstream, villagers take tourists for canoe rides through the mangroves that surround their homes. This has brought an additional source of income to the residents as they give rides and sell snacks to visitors.

Having become a more popular tourist destination, visitors come through the village on their way to the lake to see a stunning sunset over lake Tonle Sap.

Our day at the village was certainly something we’ll never forget. Jeff was so impressed he stated that he wants to move back here and live in the village for a year to see it through an entire cycle of water and drought. “I can teach at the school here!” he said with a smile. I think we all felt that this was a place we could return. But there was something here we still had to see.