Our car was parked at the village as we waited inside for our guide to give us the signal we could come out. Looking around at the homes clustered in a small grouping, each on a raised platform, I noticed again the distinctive Vietnamese red flag with single yellow star hanging outside the houses. It wasn’t surprising. We had seen flags posted in front of businesses, homes, or along the roadside since our departure from Hue earlier that morning. The coming Tet Holiday (marking the lunar new year) had the entire country preparing for festivities – including a patriotic celebration marking 50 years since the famous Tet Offensive of 1968.

Looking about we saw curious faces peering out of the double wide doorways to each home. Chickens wandered plucking at grains hidden in the dirt around the village. Our guide motioned for us it was OK to come along and we got out of the car and began our walk through this village. We smiled shyly in greeting at the curious faces that watched the five of us walking through their normally private village. Suddenly, a boy in a group of children intently watching us, shouted, “Hello!” Happy to have a greeting to respond to, I replied, “Hello!” The boy and his gang of friends dissolved into exuberant giggles.

This was a village of the Bru people, an ethnic minority (their population in Vietnam is estimated to be only around 75,000) potentially descendant from the Khmer who now live in small isolated villages scattered throughout the hillside regions of Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.

We hurried to catch up to our guide as we had only been given permission to cross through this area to get to our intended destination. Turning the corner, Hill 689 was in front of us.

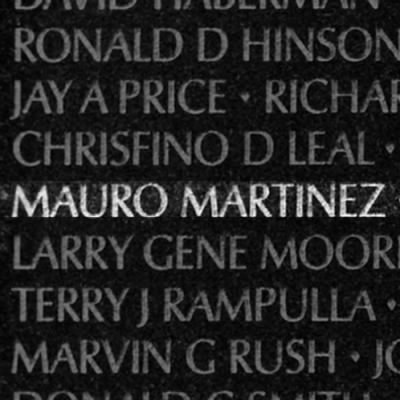

Mauro Martinez

I first heard about Mauro a week after meeting Jeff. Though he had never met his Uncle, Jeff admitted a special connection to him. It was clear through the memorabilia and stories shared about this absent Uncle that this was true of his entire family.

Jeff was only four days old when his Uncle was killed on a numbered hillside in central Vietnam. From stories I’ve heard told over the years by my father- in- law or other family members, Mauro was the larger than life personality that drew attention, admiration, and special favor from his family and friends. Mauro’s veteran’s memorial page is filled with posts from friends with phrases like, “high school legend”, “can’t say enough”, “an inspiration”. His accomplishments seemed to confirm these accolades. He got good grades, was a star athlete, loved his family, and was expected to go on to better things than the dusty little farm town he grew up on could provide.

This was remarkable, in part, because he was a Hispanic kid in 1960’s America. He grew up in a dirt walled adobe house among itinerant workers who most often quit school in the 8th grade to work and provide for their families. His older brother, John, led the way in many aspects through his own firsts within the family – first star athlete, first to graduate high school, first to college. But Mauro was the younger child and more attention was focused on him – he broke his brother’s state track record, he was a football All-star. I’m sure his future shone brightly before him as it did for others, but fatefully, his chosen route was to go to war. Though he received scholarship offers from Universities and could have attended schools almost anywhere I’ve been told, Mauro decided school and football could wait, he had other service on his mind.

The Hills of Khe Sanh

The silence of the hillside in front of us pulled each of us inward to our own thoughts. A slight wind rustled the tree leaves while a pig grunted in the field below. Several birds chirped out calls to each other. What wasn’t heard were sounds from vehicles, planes, motors, or modern life. Certainly not what I can only imagine were the deafening sounds of war that filled these hills 50 years ago.

We hired our guide before arriving in Vietnam. He came recommended online as someone who was experienced in Military history and had taken (in years past) veterans around to revisit battlefields and sites from their youth. He arrived at our hotel in Hue at 7:00 am that morning and told us we were in for a long day of driving as the sites we intended to see were far flung across the central area of Vietnam. One of the first stops along our route was Khe Sanh, the site of the infamous battle and siege that captured the American public’s attention, and if it wasn’t before, brought the Vietnamese war squarely into the living room of every American home.

Hill 689 was part of the battle of Khe Sanh as were all the hills surrounding this former US Military Base but are not part of the Khe Sanh museum. At first, when we asked our guide about going to Hill 689 he refused, saying it was impossible. All of these hills required government permits to access or were too dangerous with potential unexploded ordnances. He also pointed out there was no way we could go on this search and have time to visit the DMZ, tunnels, and other historic military sites of Central Vietnam. Not knowing how or if we should push our luck, we admitted that we were happy to visit these historic sites, but really it wasn’t our primary goal. What we really wanted was to find Hill 689.

We must have made a convincing case because despite the inconvenience, the lack of plans, and the rainy day – our guide started asking around. Driving through the village of Khe Sanh, he veered off the road and started the climb into the hills. His military history proved valuable as he able to recite historic events and battles as well as the course of the conflict to us at almost every roadside turn. We drove through red dirt trails, deeper into the hillside terrain.

Looking around, the growth of trees and plants was thick across the hills and valleys. Tall pine trees stood at the top of the hills. We stopped to confirm our direction and our guide asked an older man wearing a camouflage shirt walking on the side of the road for directions. The man eagerly nodded and pointed his arm, which was missing his forearm and hand, up the road. Noticing my gaze from the backseat, he smiled and told the guide he lost his arm to the Chinese in the Sino Vietnamese war of the late 1970’s and not the “war” as the lengthy, divisive, and turbulent unification of North and South Vietnam is simply referred to by locals today.

1968 Vietnam

The Vietnam war took a decisive turn in 1968 during the Tet Offensive, the name put to the military campaign that brought North Vietnamese forces into South Vietnam through numerous guerilla attacks in cities throughout the country. Most of the foreign military presence in the country was concentrated at the border between then North and South Vietnam – in the province known as Quang Tri – just north of the large central Vietnamese city of Da Nang. The battle/siege of Khe Sanh was part of this offensive in which the US Military base at Khe Sanh was attacked and US forces were caught in a lengthy siege and ultimate abandonment of the base. The battle lasted 5 months from the end of January to early June, 1968.

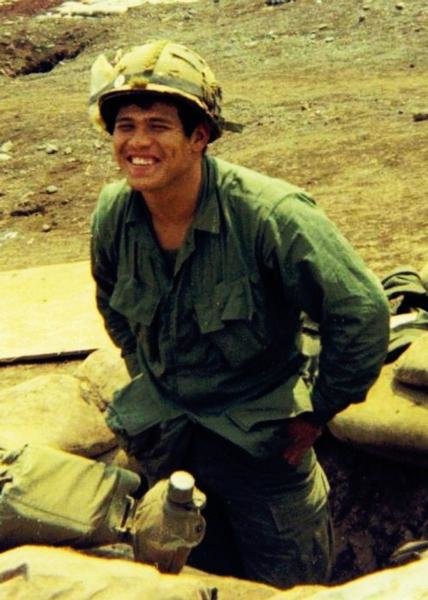

Mauro completed basic training and officially became a Marine on December 10, 1967. After spending some time at home with family he must have been sent to Vietnam in late December or early January. Conflicting or mis-remembered stories fill the first few months of his time in Vietnam. There are reports of letters home with pictures of Mauro and others in his unit. Sometime in March or April he was assigned to Hill 689. The hills surrounding Khe Sanh were the high ground that American forces sought to control and maintain to allow for the defense of the base. On the morning of April 16, Mauro’s unit was due to be helicoptered out of the hill but was ambushed by north Vietnamese forces and suffered numerous casualties. Mauro was killed by an explosion, and according to eye witness reports within his unit, as he threw his body across another Marine to cover him from incoming fire from the North Vietnamese.

When I told our guide the Marine company and regiment that Mauro was part of (United States Marine Corp, C Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines Regiment, Third Marine Division) he said that the unit was known as The Walking Dead. A moniker given to them because their battalion sustained the highest casualty numbers in Marine Corps history.

Vietnam Today

Vietnam today is a modernizing country still recovering from the multiple wars that tore it apart 50 years ago. A focus on infrastructure development, economic progress, combined with a distinctive forward-thinking mindset that lets go of the past is prevalent in the towns and countryside. The Quang Tri province was the hardest hit province of all of Vietnam and continues to be the poorest. Driving through there you see the rural economy, the patchwork villages each finding footing again. Geographically the land, though scarred, has grown lush again and it takes a fair amount of imagination to envision the bombed out and denuded landscape of 50 years ago. Unexploded ordnance from the war have killed more than 100,000 people since the war’s end. Estimates vary, but some say it will take 1,000 years to completely clean up the chemicals and military equipment from the countrysides

Throughout our stay, the subject of the war came up only a few times. A few of our guides or drivers pointed out that not as many Americans visit as they would like. The driver who took us to the Da Nang airport on our last day pointed out that the bridge we were driving by was built by the Americans and it was the only one still standing from that time. Smiling, he looked back in the rear- view mirror at us and said, “The war is behind us. We are your friends. Come back and visit.”

A Legacy

John Martinez, Jeff’s Dad, remembers being told of his brother’s death by uniformed soldiers while competing at a college track meet in Boulder. His eyes still get a distant look and his hands run through his thin hair in pent up emotion as he remembers. Shaking his head, he softly says, “what a terrible time that was.” I know he means not only losing his little brother, but the crack that it left in his family. His mother, only 45 at the time, died a couple months after learning of Mauro’s death. “She died of a broken heart”, John says.

The impact of this war on our family is not unique. Our stories, however moving, are not unique nor more important than others. They are just our stories, but through stories we remember and we learn.

When we asked our guide, what brought him into this line of work, he told us his family story. Having lived in the Quang Tri province for generations, his family was caught in the literal middle of war’s ugly path. His grandmother and aunts were killed by an American serviceman’s grenade while hiding from the forces coming through town chasing guerrilla fighters. His grandfather, who had purposefully separated his family that fateful day thinking it was safer to stay apart rather than together, survived the village raid, but was later buried alive by North Vietnamese forces who considered him an American informer. His father joined the South Vietnamese Army as soon as he was old enough, a year before the war’s final end in 1975.

What compelled us to go to Hill 689 and remember a person we’ve never met? Maybe it’s martyr-ism. In death people become larger than life and we seek to associate with their glory. Maybe it’s the desire to instill a legacy for future generations, a memory that isn’t lost to the future. Or maybe it’s a human need to connect. We see ourselves in other people’s stories and we connect with their plight. On this day, 50 years after hell and grief, our stories brought two worlds together for us – connecting all of us to our shared and much bigger story.