The best quality tea must have the creases like the leather boots of Tartar horsemen, curl like the dewlap of a mighty bullock, unfold like a mist rising out of a ravine, gleam like a lake touched by a zephyr, and be wet and soft like earth newly swept by rain. Lu Yu

Eager to rest our legs, we slid quickly into the empty seats available around the large table and gratefully accepted a small cup of tea. Our host graciously poured our next sample while tending to several other teapots brewing other samples of oolong, lychee, and green tea. The small porcelain cups barely fit in our tired hands but the subtle flavors and aroma of the tea revived our senses.

“In China we say that the mother of tea is water and the father the teapot” she explained “for both can change the nature of the tea.” With this she selected a clear glass teapot and carefully placed a small bundle of dried tea at the bottom. After brewing the water to a precise temperature with quick flicks of her electric cook stove, she tested the water’s temperature by pouring it over a clay dragon. When the water poured over the dragon, the dragon changed from a dull brown to a vivid jade green. “Now I know the water is the correct temperature” she said. She then poured this into the glass teapot. After diverting our attention back to the teacups in our hand, she told us of the subtle flavors found in each sample. For our last tea she showed us what had bloomed in the teapot while we were focused on our teacups– a blooming flower jasmine tea.

We started the day at the China National Tea Museum in Hangzhou. As the only official tea museum in all of China, all it took was a quick flash of a name and image from our smart phone to get nod of understanding from our taxi driver. In a short but scenic taxi drive, we were taken from our hotel in Hangzhou to the foothills of the mountains where tea plantation stood, glimmering with dew in the early morning sunshine.

The tea bush fills the hills around Hangzhou where the most famous tea of China (at least according to the people in this region) is grown. Longjing, or Dragon Well tea, is a famous and popular green tea which gets its name from the local spring near the plantation.

The China National Tea Museum sits in a sprawling tea plantation and each building on the museum grounds walks you you through the cultivation and culture of tea from its origins to present day use. As we learned from the Shanghai Museum, it seems the best museums in China are free of charge. China is rightfully proud of its tea heritage – being the inventors of a culture of tea drinking that has spread worldwide. Lu Yu, known as the Sage of Tea throughout China, wrote the book, The Classic of Tea in the 8th Century AD. That this book is still used as a resource today – some thousand years later – indicates how perfected a craft the culture of tea is in this country.

The museum sits tucked within rolling tea fields and in the distance you can see the city of Hangzhou. Paths wind their way from building to building which house great displays (in both Mandarin and English) that explain the history of tea. You learn things such as China’s first tea was a tea tree, massive and sweeping, to the method of cultivation (the first processing of tea produced bricks and wheels that were used almost as currency) to the wide variety of now cultivated tea.

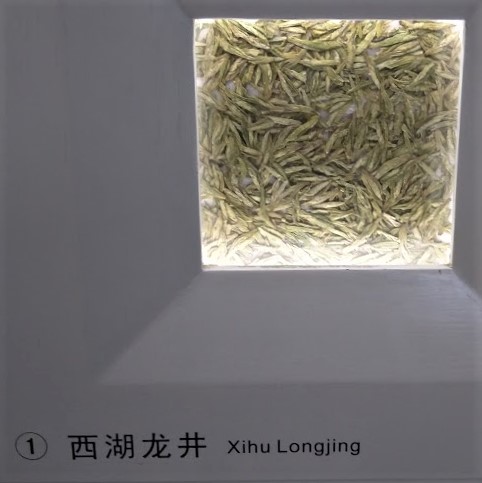

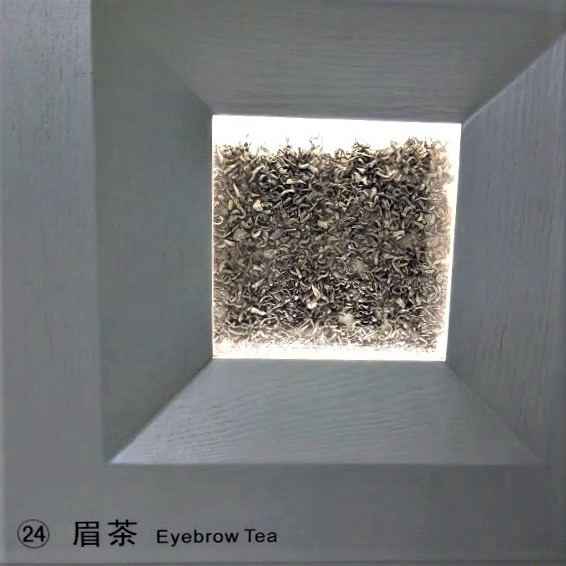

While tea technically is a beverage brewed from a tea leaf, in China (as in many places) tea drinking includes beverages brewed from other flowers and herbs like chrysanthemum, jasmine, and almost a limitless range of other types. One hall in the museum has walls filled with box after box displaying the many, many tea varieties found in China.

In addition to the many varieties of tea, there are numerous types of teapots and tea cups ranging from clay, iron, and porcelain. However, the most common way to drink tea in China is in a small clear glass with the tea floating free, not bound by a teabag or strainer. Teatime snacks include the ever present sunflower seeds and other small dried fruits. You drink your tea by carefully straining the tea in your mouth or, as some do, simply chewing up any pieces that get into your mouth.

We had picked up a pamphlet when we entered the museum and had used it as we made our way through the museum grounds. I saw that the map indicated a trail that wound its way around the tea plantation and spotted a paved pathway leading up and around the hillside. We started on the climb and eventually the trail tucked into the forest above the tea fields and veered off to the left. Each bend in the path appeared to mimic (at least in my mind) the bend in the map.

Though the path was steep and seemed to keep climbing and climbing, we assumed it had to wrap around eventually so we succumbed to the “it must be just around this bend” or “let’s see what’s at the top of the next hill” suggestions that we kept telling ourselves. The path was clearly “a path”. It was paved with carefully measured and laid stones and had even stairs climbing the hills.

After getting out of breath on yet another hill, I began to wonder if we had stumbled on China’s version of the Appalachian trail – just idyllically paved and manicured over thousands of years of travel. An hour later, we stopped the first person we saw and asked (showing the map) if the trail ever ended up again at the tea museum. He pointed to a fork in the trail and told us to go that way.

Finally turning left and winding our way down the ridge and mountain line, we came out to the roadside and a restaurant. The Tea Museum was nowhere in sight.

It took us another long walk and a bus ride to eventually work our way BACK to the museum. Once there I asked the information desk attendant about the trail that I had intended hike – pointing to my map on the museum’s pamphlet. She said in broken English, “Oh, that isn’t THIS museum. This map is to another museum we have that is in the mountains about 30 or 40 minutes up the road.”

That’s when we decided to give it up to the experts – those who have learned before through trial and error – and simply enjoy a good cup of tea.